Cemented vs. Screw-Retained Restorations: A Balanced Perspective

In implant dentistry, few topics generate as much debate as the choice between cemented and screw-retained restorations. Having been trained during the early years of modern implantology, I have experienced both approaches firsthand — and the ongoing controversy continues to fascinate me.

From “Old School” to New Protocols

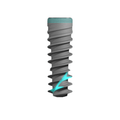

My initial training was very much “old school”: most restorations were cemented, especially when UCLA castable abutments became available. At that time, restorative protocols resembled traditional crown-and-bridge dentistry, where cementation was the norm. Over the years, as implant systems and abutments evolved, restorative concepts shifted dramatically toward screw-retained solutions.

But does that mean today we should exclusively use screw-retained restorations? The answer is more nuanced. In my practice, I continue to perform both — cemented and screw-retained — depending on the case.

What Does the Literature Say?

The supposed “radical” shift came from the belief that all cemented restorations inevitably cause peri-implantitis. However, clinical evidence tells a different story. Most studies show no statistically significant difference in biological outcomes between cemented and screw-retained restorations.

What the literature does suggest is:

-

Cemented restorations may carry higher biological risks, mainly from excess cement.

-

Screw-retained restorations may carry higher mechanical risks, such as screw loosening or framework misfit.

Understanding Biological vs. Mechanical Risks

-

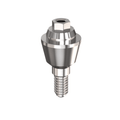

Biological complications often result from poor cement removal or improper abutment selection. If the abutment’s transmucosal height is too low, the finish line ends up deep subgingivally, making cement removal nearly impossible.

Ideally, the margin should be equigingival or 0.5 mm subgingival. Retraction cords, rubber dam isolation, or cementing extraorally on a die can further minimize risks.

-

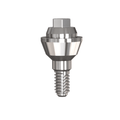

Mechanical complications in screw-retained cases mainly involve screw loosening or prosthetic misfit. Proper torque application is essential to reduce these risks.

-

Hybrid prostheses present their own challenges: a concave design against the mucosa can create significant biological problems if not carefully managed.

Clinical Considerations

Several practical factors influence the decision:

-

Screw access position: If the emergence is buccal, screw retention is not feasible. Ideally, the screw channel should exit palatally or at the cingulum in anterior teeth.

-

Posterior restorations: If the screw access is located on a functional cusp rather than the central fossa, cementation may be the safer choice.

-

Esthetics: Some patients are highly sensitive to the appearance of a screw access hole.

Advantages and Limitations in Practice

-

Screw-retained restorations are retrievable — valuable when replacing a broken restoration or managing peri-implantitis. However, every time the prosthesis is removed, the screw should be replaced, adding to long-term costs.

-

Cemented restorations remain relevant and, in some cases, can even be modified into “cement-screw” restorations if access is possible.

Conclusion

While screw-retained restorations have become the preferred choice in many protocols, cemented restorations still play a vital role in modern implantology. The final decision should balance scientific evidence, clinical factors, and — importantly — the patient’s esthetic and functional expectations.

Warm regards,

Dr. Bernardo Grobeisen

0 comments